DJ Three reflects on the twists of fate that brought TRiP MAGAZEEN back into print, the legacy of vinyl, and why underground culture only thrives when people are willing to build it themselves.

DJ Three has been holding the line for underground electronic music in the U.S. since emerging from Florida in 1990, as rave culture was about to explode. Over the past three and a half decades, he’s built a global reputation as one of America’s most respected DJs, known for an eclectic approach fueled by record stores, warehouses, clubs, and tireless nights behind the decks.

His rare but celebrated production credits include classic remixes as Montage Men, Three A.M., and the Multiple Mirrors EP by Second Hand Satellites. He’s also been involved in or at the helm of three of the most beloved American underground record labels from 1992 through the present day: Hallucination Recordings, Hallucination Limited, and Hallucienda.

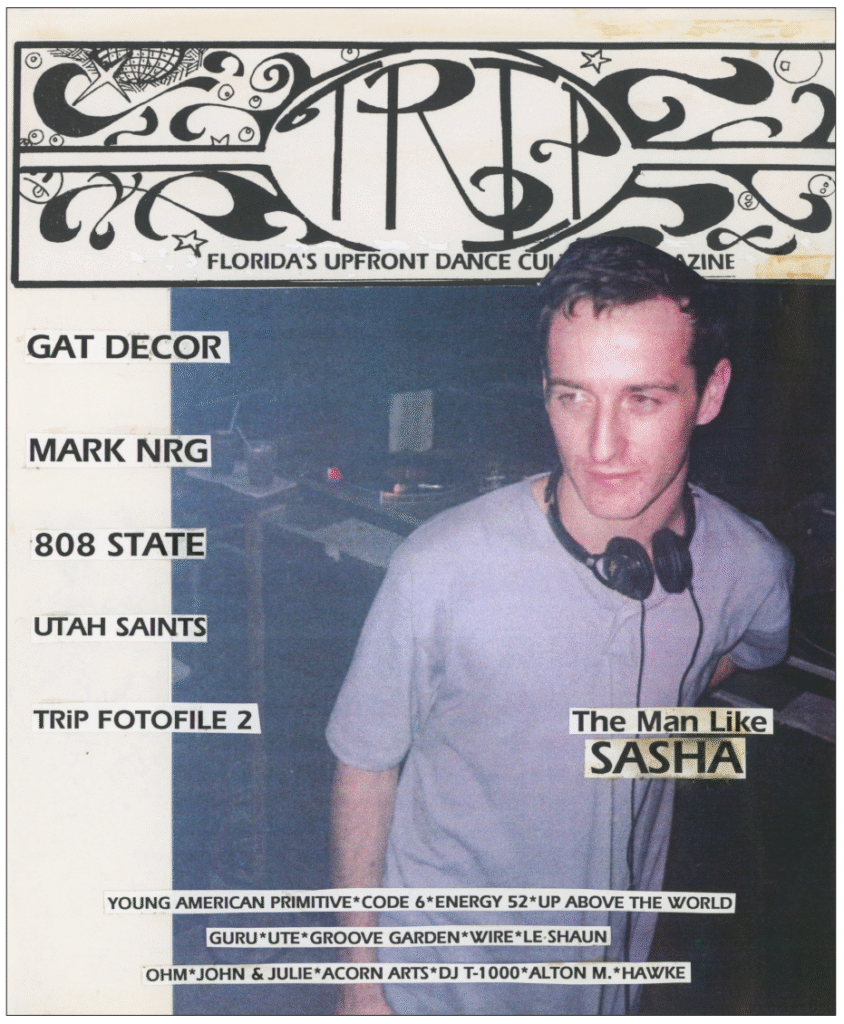

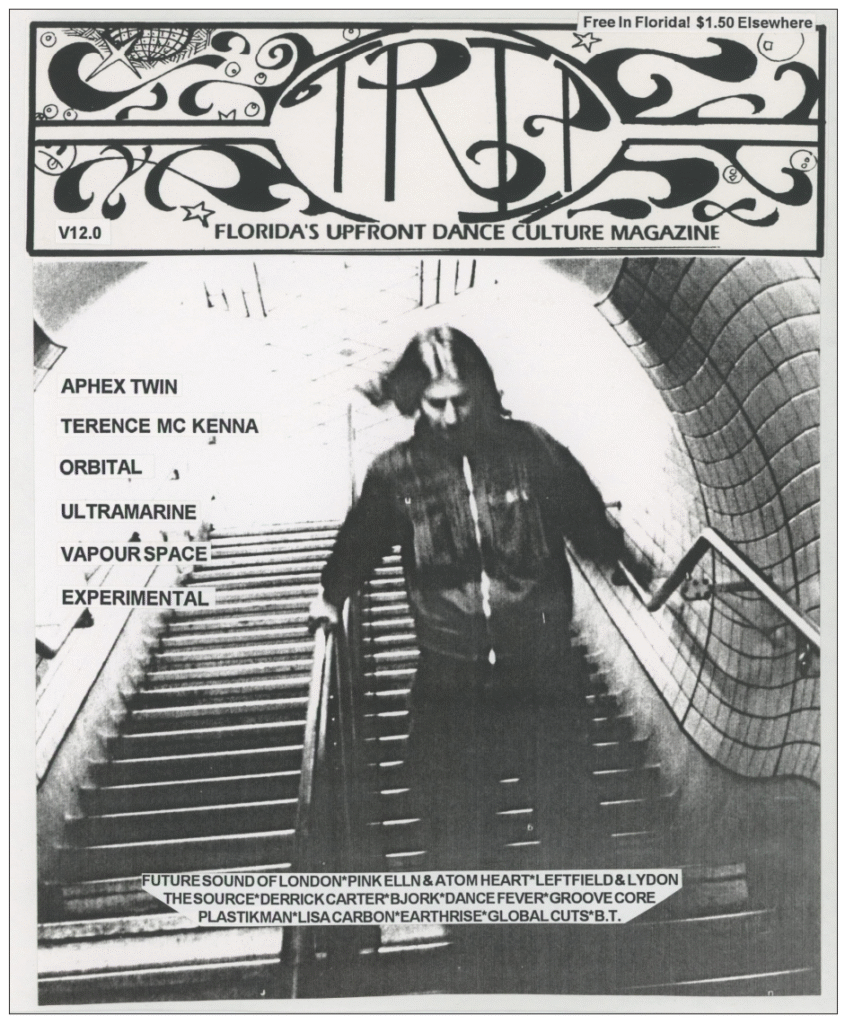

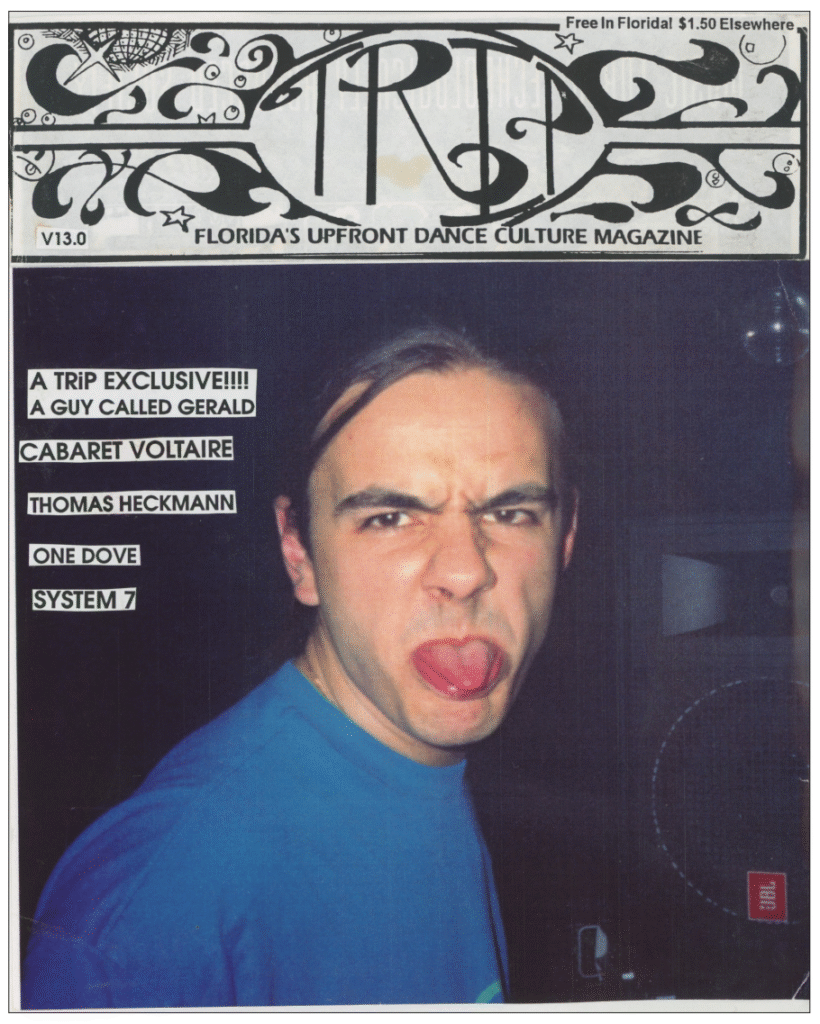

In 2025, DJ Three celebrated 35 years behind the decks with the release of TRiP MAGAZEEN: The Complete Collection, a 350-page archival volume published by DJ DB’s Blurring Books.

Created with founder Peter Wohelski and Grumptronix, TRiP documents the formative years of U.S. rave culture and the global electronic sounds that fueled it from 1992 through 1994—before the internet and before algorithms. Across 16 issues, the zine captured a scene in motion through hundreds of record reviews, interviews, and firsthand reports, which now read as early snapshots of artists on the brink of defining an era.

In this conversation, DJ Three reflects on the twists of fate that brought TRiP MAGAZEEN back into print, the beginnings of Florida rave culture, the legacy of vinyl, and why the underground only truly thrives when people are willing to build it on their own.

instagram.com/djthreeofc

https://soundcloud.com/djthreeofc

facebook.com/djthree

Across 16 issues, never before compiled online or in print, TRiP traverses the underground through the eyes of its progenitors during the peak and dissolution of Rave as a major label commodity.

Around 2017, I started hitting Peter up about doing something with TRiP. We discussed creating a social media page for it and maybe making a dedicated web archive. We had that conversation about once a year until the pandemic began in March 2020, and that was the closest we got to actually doing anything.

Enter Forest Gilbakian, a guy in New York we’ve come to see as a sort of rave archivist. He hit up Peter a couple of times trying to complete his TRiP collection, and said he’d seen issues going for $150 on eBay. I think Peter was more preoccupied with getting through 2020 at the time, and not much came of it.

Eventually, it turns out that Forest knows the son of DJ DB (DB Burkeman), the UK ex-pat and New York rave pioneer who now owns the Blurring Books publishing company. Still trying to complete his collection, Forest enthusiastically brought up TRiP to DB and suggested he try to make a book out of it.

That twist of fate is what ultimately led to the book being published. Peter still had all the print mats and sent them to DB, who was blown away. I just happened to call Peter again around the time DB had expressed interest in doing the book, and here we are!

Another twist is that DB and Peter were rival New York record label A&Rs in the mid ‘90s—DB at Sm:)e Communications and Peter at Astralwerks—a job Peter got largely as a result of doing TRiP MAGAZEEN.

When I first got the book in my hands, what struck me the most—some thirty years later—is how relevant and timeless it feels. It was a foundational time. Many artists in TRiP had just done or were about to do their most iconic works. You can’t turn your head today without seeing another reissue from that era—big ones like Lifeforms from Future Sound of London, Selected Ambient Works from Aphex Twin, and so many lesser-known or obscure 12” releases.

In his book review for The Wire, Joe Muggs says “the many hundreds of reviews have an impressive strike rate,” making TRiP serve as a “useful buyer/streamer’s guide.” He’s not wrong. I’ve even been sourcing music to DJ for the very first time from it myself.

Actually, in the middle of reading a review Grumptronix wrote, I realized it was about a track I’ve been trying to remember—that might never have happened otherwise. But yeah, you can literally turn to any page and find something interesting about artists, labels, and music. Not to mention the scene reports in there, giving a glimpse of how it all was going down.

And while TRiP wasn’t America’s first electronic zine, I agree with DJ DB saying it’s the most comprehensive and enduring of that era. Our eclectic background in the alternative dance music scene heavily influenced our approach to rave culture, and that’s why TRiP comfortably featured everyone from Cabaret Voltaire and Bill Laswell to Laurent Garnier and The Orb.

I might be a little long-winded here.

I started DJing in alternative dance music clubs in Tampa in 1990. A bit of acid house, techno, and new beat had been mixed in with the industrial and post-punk prior to that. But this new hardcore rave sound was creeping into everyone’s sets.

I went to Los Angeles for a couple of weeks around New Year’s Eve 1991 to see what American raves were really like, expecting to be too overwhelmed to think I could really DJ in that world. But instead, I heard records I already owned and DJs making mistakes. That’s when I thought, “Hold on, I think I can actually do this”.

Peter was a longtime alternative music radio DJ on 88.5 FM in Tampa and had connections in the music industry. We loosely knew each other in the alternative club scene. He went to London for a year in 1991 to work with Jay Patrick Ahern (Aquarhythms/Modular Cowboy and eventual TRiP contributor) and immediately fell into UK rave culture.

When he got back to Florida, he decided, in the spirit of punk zines like Maximum Rocknroll, to put his journalism degree to use and make an electronic zine. He caught wind that we were throwing the first one-off style raves in the Southeast: The Raven in December 1991 and MANIC Raven II in March of 1992, which was Moby and Doc Martin’s first Florida rave gig.

When I saw the first issue of TRiP, I called the phone number inside and left a message wanting to know who was behind it. We quickly reconnected, and I wanna say it was after Raven II that Peter asked Grumptronix and myself to get involved.

The three of us together widened the scope of music TRiP covered, and Peter took that to great ends. We all ended up communicating directly with so many of our heroes. I think it felt instinctual to not only document the scene, but also to put our musical perspective on full display. We wanted to push a more eclectic mindset

Musically speaking, 1992 was already the first commercial peak in relation to rave culture. The major labels had repackaged all types of “hardcore techno” from around the world as a new genre called “rave,” which literally peaked and dissolved during the course of TRiP’s existence, while the underground kept rolling forward with endless mutations of house and techno.

Out of British hardcore came jungle techno, jungle, and drum and bass as new forms of music. The foundation of house and techno had already become a musical exquisite corpse, if you will.

After any new arc in dance music subsides, whatever’s good from it always seeps into house and techno. Subgenres absorb elements or morph, like how progressive house gave way to progressive trance in the ‘90s. Then history repeats, and some trends reanimate themselves. Like now, you see a lot of purists bemoaning the post-pandemic wave of hardcore techno, and I think they either don’t recall or don’t realize this is what “rave” music was. Hardcore techno—this so-called bastardized mutation—was the predominant soundtrack as raves went global in the early ‘90s, and it permeated all styles to some degree. Jeff Mills even had a residency alongside DJ Repete at The Limelight.

Nobody should be surprised that 35 years later, a new generation has reimagined that model into something of their own again.

As for that era in Florida, what often gets left out of American rave history is that there was a foundational blueprint before one-off raves even existed there. Kimball Collins and Dave Cannalte were playing all night into the next morning at The Beacham Theatre as far back as early 1989, and pure MDMA was already flowing into Florida.

The Beacham was ground zero for what would become Florida rave culture. I don’t want to say it was more sophisticated, but it was more unique, not least of which because it was every Saturday night in a converted 1920s-era theatre.

People were driving from all over the state just by word of mouth to stay well past sunrise, like they’d eventually do for one-off raves and club nights. The Beacham was moving in this direction before Kimball’s arrival, with the previous DJ Jo Ed inspiring him in 1988.

It eventually became known as AAHZ, and the music was very heavily influenced by what was being played in the UK—no coincidence, as it’s where rave culture began.

If American rave culture had a club parallel to something like Junior Vasquez’s Sound Factory in New York, there’s no question it was The Beacham Theatre. The size of the club, hours of operation, same DJ every week, and their unique musical thumbprints—just with completely different demographics. It was literally the first place in Florida where thousands of people experienced underground dance music in this fashion. The fact that they still, to this day, have a sold-out once-a-year “AAHZ Reunion” is a testament to its impact.

Simons in Gainesville opened in late 1990, but there still hadn’t been any “one-off” style raves in Florida until we threw The Raven in December 1991 in a warehouse in St. Petersburg. Initially, it was only going to be myself, Steve McClure (before he was DJ Monk), and Grumpy C (Wayne Consiglio, before he became Grumptronix) as the DJs.

But the buzz grew quickly, so we decided to invite DJs from all over Florida to play: Chang from Miami, George St. Pierre and Brian Bright from Tallahassee, Andy Hughes from Orlando, Bruce Wilcox from Simons—I can’t even recall everyone. David Christophere (Rabbit in the Moon) and I reworked some existing material he had and performed it live. Around 650 people in a warehouse in St. Pete. Some people still even have the t-shirt we made. Shortly after this, in 1992, is when David and Monk would start Rabbit in the Moon.

For context about how big the music itself was becoming on major labels before the one-off raves and club nights started, I should point out that there were a few really impactful concert tours coming through Florida before we threw The Raven.

There was the Mute Over America tour with Renegade Soundwave (live) and DJ Derrick May in April 1991—it wasn’t rammed, but Derrick left an indelible impression on every DJ who witnessed him. Romulo of Schematic brought this up at a TRiP talk in Miami recently, then Deee-Lite came in May, and 808 State in September. Those latter two were epic shows, and they were the first time I DJ’d only this music to huge crowds.

The Shamen brought their “Progeny” tour in February 1992. It was like a touring club night, and it was rammed—everyone was curious to check out this music by then. That was a month before we did Raven II with Moby (live) and Doc Martin’s first-ever Florida gigs.

The Shamen only played Tampa and Orlando, so David Christophere and I went to Miami the week prior to promote. That brought tons of people up and led to UK ex-pat David Beynon—who was kickstarting raves in Miami pretty much concurrently with us—to organize a couple of buses of people to Raven II. Matt E. Silver of Dance Music Report actually flew in to cover Raven II. All this was happening as AAHZ was peaking before it stopped.

By April ‘92, the floodgates blew open—one-off raves and club nights with multiple DJs were happening all over the state. Between the ground zero years of The Beacham Theatre, Simons, and the music having a push through mainstream channels during that time, Florida just exploded into the rest of the ‘90s.

By then, I was sure I didn’t really want to be a promoter. Established clubs were already calling the cops on one-off parties in Tampa—the old guard versus the new guard—but this music quickly took over the clubs anyway. I was focused on DJing, TRiP, and eventually helming the newly formed position of “dance music buyer” at The Alternative Record Store in Tampa. By the end of 1992, I was DJing at the first large-scale raves in the Southeast, like Infonet 1 in Orlando—which was organized by a then post-AAHZ Kimball Collins—and Psychic Energy in Atlanta.

That’s tough to say, because there are plenty who weren’t as big as Future Sound of London and Aphex Twin at the time, but they’re all still notable names to me.

J. Saul Kane of Vinyl Solution was someone we really looked up to in underground dance music. Others would be Damon Wild from Experimental and now Synewave Records, Kenny Larkin, Terre Thaemlitz in his Comatonse ambient days, Mark Gage as Vapourspace, Sean Deason from Matrix in Detroit, and Thomas Heckmann.

In hindsight, what really stands out to me is how forthright the bigger artists were with us. They weren’t talking to a major journalist or publication looking for a pull quote—what we would now call clickbait for the cover. They were talking to us as fellow DJs, artists, record store people, and label people.

If you compare our Aphex Twin interview to Simon Reynolds’ interview from the same period, the topics overlap, but the tone is noticeably different. Richard is more casual and forthright with TRiP. The same goes for the two Future Sound of London interviews. Both the Lifeforms and Dead Cities albums had just been completed, but were still unnamed for each interview, respectively.

Capturing so many artists at the moment they were delivering benchmark releases makes those interviews even more special. It still excites me.

Exponentially.

Being the electronic and dance music buyer at Alternative Record Store in Tampa back in the ‘90s gave me access to an incredibly wide range of music—house, techno, jungle, hardcore, drum & bass—and a direct pipeline to distributors like Watts Music. It directly informed everything I was doing as a DJ.

What surprised me was that a lot of the records I was most excited about in the store were the ones customers weren’t really into. But then I’d play them out, and a lot of those same people would come up to the booth asking, “What is that?”

In my head, I’m thinking: “You hated this in the shop.” That’s when I started to feel like something interesting was happening for me as a DJ. But it took me years to feel more confident about hearing things differently than the other DJs while still getting a huge reaction on the dancefloor.

By the mid-to-late ’90s, I was drawing crowds like the other big DJs in Florida, but I still felt like the black sheep. Most DJs seemed to be chasing the same promos, acetates, and white labels. While I liked some of those records, I think I was looking at music through a more global lens, while a lot of the scene in Florida felt overtly UK-focused.

Record store culture could be notoriously difficult back then. You walk into the wrong shop and ask for the wrong record, and people could be dismissive. I never wanted to be that guy at The Alternative Record Store. If someone asked what the “cool” record of the week was, I’d ask what they were into first.

That mindset was the heart of TRiP MAGAZEEN. We realized early on that everything was splintering into tribes based on social groups and what was hip, and we wanted to push against that. It didn’t have to be like high school. You could just have eclectic tastes!

That approach fueled me both as a DJ and in how I tried to influence the culture as a record buyer. I always encouraged people to go with their gut.

The short answer is yes, but there are layers to it.

There’s no denying the tactile side of vinyl—the feeling you get from the artwork or reading the credits.

Streaming has become the predominant way people listen to music in the modern world.

Unfortunately, because of how platforms like Spotify have geared it, most people don’t even know what they’re listening to. They just know it’s their “chill hip hop playlist.” The focus is built by prompts or algorithms, rather than artists or albums. And for some, the idea of listening to a full album barely exists anymore.

You want people to be able to interact with and pay for music however they want. It varies individually, generationally, and by medium. It all comes down to preference.

Great music will always find a way to resonate with people, regardless of what shape or form it comes in. I do think vinyl is a visceral way to experience it in more ways than one.

Vinyl is a legacy way of playing, and you don’t want to see the DNA of the art form completely disappear. But I’m not precious about it, and I don’t think anyone should be. When vinyl-only was becoming a hot topic again, Craig Richards said, “Vinyl only is the new MP3.”

For me, it doesn’t matter how you play, but how it translates in the room. You can’t fake content, you can’t fake character, and you can’t fake intuition. Vinyl is just how I prefer to play when I can.

At this point, I’d say vinyl DJing tends to be more about the momentum of the mix, and digital DJing tends to be more about a segue between two tracks. That’s a generalization, but it’s usually true.

What I love about vinyl DJing is that it can be anything—long mixes, short mixes, or re-editing with two copies of a record—but it all unfolds over each track selection. With digital DJing, it’s easier to fall into a pattern of EQ cuts into loops, hot cues, FX, and drops where the emphasis shifts away from momentum and tends to almost exclusively be about that kind of segue or drop between tracks.

When you’re playing vinyl, you have to be willing to die on the hill of the last track you put on, whereas digitally, you don’t. You can make a loop, put in a big swoosh, and get out of anything instantly. I’m not saying that one way or the other is the only way, but stylistically, it’s different.

I love playing records. It feels the most natural, and always has. When I’m on CDJs, I try to play with the same feel—to just play the music with that kind of momentum. I don’t even use Rekordbox. Sounds crazy to most people, but I know I’m not the only one.

After going through the book, one of the biggest takeaways I had was how many things have actually not changed. As early as 1994, everyone was up in arms about the commercialization and corporatization of the scene, and how everyone’s doing it for the wrong reasons or the wrong way. That conversation hasn’t ever gone away.

Some people predicted festival culture would shorten attention spans. I always felt like that didn’t matter as long as there were clubs. Now that many clubs are struggling or have closed, that’s a real bummer. Clubs are where you get a more focused presentation—a DJ playing a longer set, or DJs playing together as a group.

What we need to protect is the same thing we’ve always needed to protect: the willingness to build the culture yourself.

You can’t just expect to tour and have everything the way you want it. If you’re a DJ, throw your own parties in your local scene if and when you can. That’s where most of us came from.

You can go out there and tout that the way you’re doing it is the best and everything else sucks. Or, you can just present what you’re doing and why you’re doing it.

Across 16 issues, never before compiled online or in print, TRiP traverses the underground through the eyes of its progenitors during the peak and dissolution of Rave as a major label commodity.